Sleepons have one principal advantage over condvars. Suppose that you want to synchronize many objects. With condvars, you'd typically associate one condvar per object. Therefore, if you had M objects, you'd most likely have M condvars. With sleepons, the underlying condvars (on top of which sleepons are implemented) are allocated dynamically as threads wait for a particular object. Therefore, using sleepons with M objects and N threads blocked, you'd have (at most) N condvars (instead of M).

However, condvars are more flexible than sleepons, because:

- Sleepons are built on top of condvars anyway.

- Sleepons have the mutex buried in the library; condvars allow you to specify it explicitly.

The first point might just be viewed as being argumentative. :-) The second point, however, is significant. When the mutex is buried in the library, this means that there can be only one per process—regardless of the number of threads in that process, or the number of different “sets” of data variables. This can be a very limiting factor, especially when you consider that you must use the one and only mutex to access any and all data variables that any thread in the process needs to touch!

A much better design is to use multiple mutexes, one for each data set, and explicitly combine them with condition variables as required. The true power and danger of this approach is that there is absolutely no compile- or runtime checking to make sure that you:

- have locked the mutex before manipulating a variable

- are using the correct mutex for the particular variable

- are using the correct condvar with the appropriate mutex and variable

The easiest way around these problems is to have a good design and a design review, and also to borrow techniques from object-oriented programming (like having the mutex contained in a data structure, having routines to access the data structure, etc.). Of course, how much of one or both you apply depends not only on your personal style, but also on performance requirements.

The key points to remember when using condvars are:

- The mutex is to be used for testing and accessing the variables.

- The condvar is to be used as a rendezvous point.

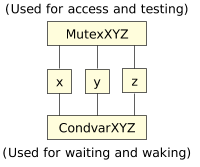

Here's a picture:

Figure 1. One-to-one mutex and condvar associations.

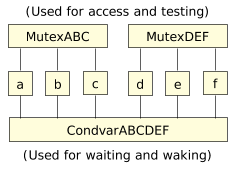

Figure 1. One-to-one mutex and condvar associations.One interesting note. Since there is no checking, you can do things like associate one set of variables with mutex “ABC,” and another set of variables with mutex “DEF,” while associating both sets of variables with condvar “ABCDEF:”

Figure 2. Many-to-one mutex and condvar associations.

Figure 2. Many-to-one mutex and condvar associations.This is actually quite useful. Since the mutex is always to be used for “access and testing,” this implies that I have to choose the correct mutex whenever I want to look at a particular variable. Fair enough—if I'm examining variable “C,” I obviously need to lock mutex “MutexABC.” What if I changed variable “E”? Well, before I change it, I had to acquire the mutex “MutexDEF.” Then I changed it, and hit condvar “CondvarABCDEF” to tell others about the change. Shortly thereafter, I would release the mutex.

Now, consider what happens. Suddenly, I have a bunch of threads that had been waiting on “CondvarABCDEF” that now wake up (from their pthread_cond_wait()). The waiting function immediately attempts to reacquire the mutex. The critical point here is that there are two mutexes to acquire. This means that on an SMP system, two concurrent streams of threads can run, each examining what it considers to be independent variables, using independent mutexes. Cool, eh?