To keep things clear, I've avoided talking about how you'd use message passing over a network, even though this is a crucial part of QNX Neutrino's flexibility!

Everything you've learned so far applies to message passing over the network.

Earlier in this chapter, I showed you an example:

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int

main (void)

{

int fd;

fd = open ("/net/wintermute/home/rk/filename", O_WRONLY);

write (fd, "This is message passing\n", 24);

close (fd);

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

At the time, I said that this was an example of “using message passing over a network.” The client creates a connection to a ND/PID/CHID (which just happens to be on a different node), and the server performs a MsgReceive() on its channel. The client and server are identical in this case to the local, single-node case. You could stop reading right here—there really isn't anything “tricky” about message passing over the network. But for those readers who are curious about the how of this, read on!

Now that we've seen some of the details of local message passing, we can discuss in a little more depth how message passing over a network works. While this discussion may seem complicated, it really boils down to two phases: name resolution, and once that's been taken care of, simple message passing.

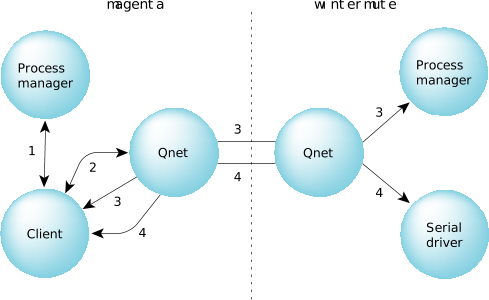

Here's a diagram that illustrates the steps we'll be talking about:

Figure 1. Message passing over a network. Notice that Qnet is divided into two sections.

Figure 1. Message passing over a network. Notice that Qnet is divided into two sections.In the diagram, our node is called magenta, and, as implied by the example, the target node is called wintermute.

Let's analyze the interactions that occur when a client program uses Qnet to access a server over the network:

- The client's open() function was told to open a filename that happened to have /net in front of it. (The name /net is the default name manifested by Qnet.) This client has no idea who is responsible for that particular pathname, so it connects to the process manager (step 1) in order to find out who actually owns the resource. This is done regardless of whether we're passing messages over a network and happens automatically. Since the native QNX Neutrino network manager, Qnet, “owns” all pathnames that begin with /net, the process manager returns information to the client telling it to ask Qnet about the pathname.

- The client now sends a message to Qnet's resource manager thread, hoping that Qnet will be able to handle the request. However, Qnet on this node isn't responsible for providing the ultimate service that the client wants, so it tells the client that it should actually contact the process manager on node wintermute. (The way this is done is via a “redirect” response, which gives the client the ND/PID/CHID of a server that it should contact instead.) This redirect response is also handled automatically by the client's library.

- The client now connects to the process manager on wintermute. This involves sending an off-node message through Qnet's network-handler thread. The Qnet process on the client's node gets the message and transports it over the medium to the remote Qnet, which delivers it to the process manager on wintermute. The process manager there resolves the rest of the pathname (in our example, that would be the “/home/rk/filename” part) and sends a redirect message back. This redirect message follows the reverse path (from the server's Qnet over the medium to the Qnet on the client's node, and finally back to the client). This redirect message now contains the location of the server that the client wanted to contact in the first place, that is, the ND/PID/CHID of the server that's going to service the client's requests. (In our example, the server was a filesystem.)

- The client now sends the request to that server. The path followed here is identical to the path followed in step 3 above, except that the server is contacted directly instead of going through the process manager.

Once steps 1 through 3 have been established, step 4 is the model for all future communications. In our client example above, the open(), read(), and close() messages all take path number 4. Note that the client's open() is what triggered this sequence of events to happen in the first place—but the actual open message flows as described (through path number 4).

We'll come back to the messages used for the open(), read(), and close() (and others) in the Resource Managers chapter.