Guest exits are one of the most significant sources of overhead in a hypervisor system.

It is impossible to avoid all guest exits in a hypervisor system. However, since guest exits are costly, reducing the number of these exits can improve the performance of guests and of the overall system.

Why a guest exits

When a guest is running, its instructions execute on a physical CPU, just as if the guest were running without a hypervisor. However, guests are not allowed to do everything they would be allowed to do if they were running in a system without virtualization. This is one of the ways that a hypervisor system protects itself from its guests, as well as its guests from each other.

A guests exit can be triggered by:

- the guest itself (see “Guest-triggered exits”)

- the hardware or the hypervisor host (see “Interrupts”)

The work required for a guest exit

The following presents an overview of what happens when a guest attempts to execute an instruction that it isn't permitted to execute, but which the hypervisor host can look after for the guest (assuming that the instruction will not cause the hypervisor to return an error to the guest):

- The virtualization hardware traps the attempt, and forces the guest to stop executing (guest exit).

- On the trap, the hardware notifies the hypervisor.

- The hypervisor saves the guest's context, then completes the task the guest had begun but was unable to complete for itself.

- When it has completed the task, the hypervisor restores the guest's context, updated to reflect the results of whatever task it completed for the guest.

- The hypervisor hands execution back to the guest (guest entrance). The guest is none the wiser. It may not even know that it was the hypervisor and not the hardware that completed the task (with the exception of para-virtualized devices); it doesn't even know that any time has passed since it was forced to exit (see “Para-virtualized devices” and “Time” in the “Understanding QNX Virtual Environments” chapter).

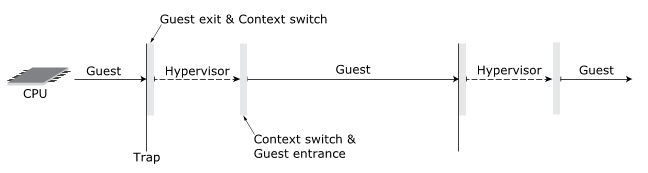

The Lahav Line below presents an overview of the guest exit–guest entrance sequence that is required every time the virtualization hardware traps a guest instruction. For simplicity, it assumes an execution path on a single CPU.

Figure 1. A Lahav Line showing how in a QNX hypervisor system execution on the physical

CPU alternates between the hypervisor and its guests. On a trap, the hypervisor

manages the guest exit, saving the guest's context, then restoring it before the

guest entrance. This diagram is the same as the one in “Two representations of a QNX hypervisor system” in the “Understanding QNX Virtual Environments” chapter.

Figure 1. A Lahav Line showing how in a QNX hypervisor system execution on the physical

CPU alternates between the hypervisor and its guests. On a trap, the hypervisor

manages the guest exit, saving the guest's context, then restoring it before the

guest entrance. This diagram is the same as the one in “Two representations of a QNX hypervisor system” in the “Understanding QNX Virtual Environments” chapter.The work is essentially the same if the hardware or the hypervisor triggers the exit: the hypervisor must save the guest's context, execute instructions on behalf of the guest, restore the guest's context, then hand execution back to the guest.

The cost of a guest exit

At each guest exit the hypervisor must store the guest's context; before each guest entrance it must restore the guest's context, updated to reflect the results of whatever task it completed for the guest.

The minimum overhead time for a guest exit–guest entrance cycle is the time the hypervisor takes to save then restore a guest's context, or, starting from the hypervisor rather than the guest, the time it takes for:

- The hypervisor to restore the guest's context and pass execution to it.

- The guest to execute a NOP instruction.

- Execution to return to the hypervisor.

Not surprisingly, the time required for a hypervisor–guest–NOP–hypervisor round-trip depends largely on the hardware. It is typically from three to 10 microseconds, depending on the SoC, but consistent on an SoC; that is, if one round trip takes five microseconds, then you can count on all round-trips during normal operation taking five microseconds, with very little variance.

Nonetheless, three or 10 microseconds repeated often enough can significantly impact a guest's performance, especially if we remember, not only that the exit uses the hypervisor's time, but also that during this time the guest is waiting.